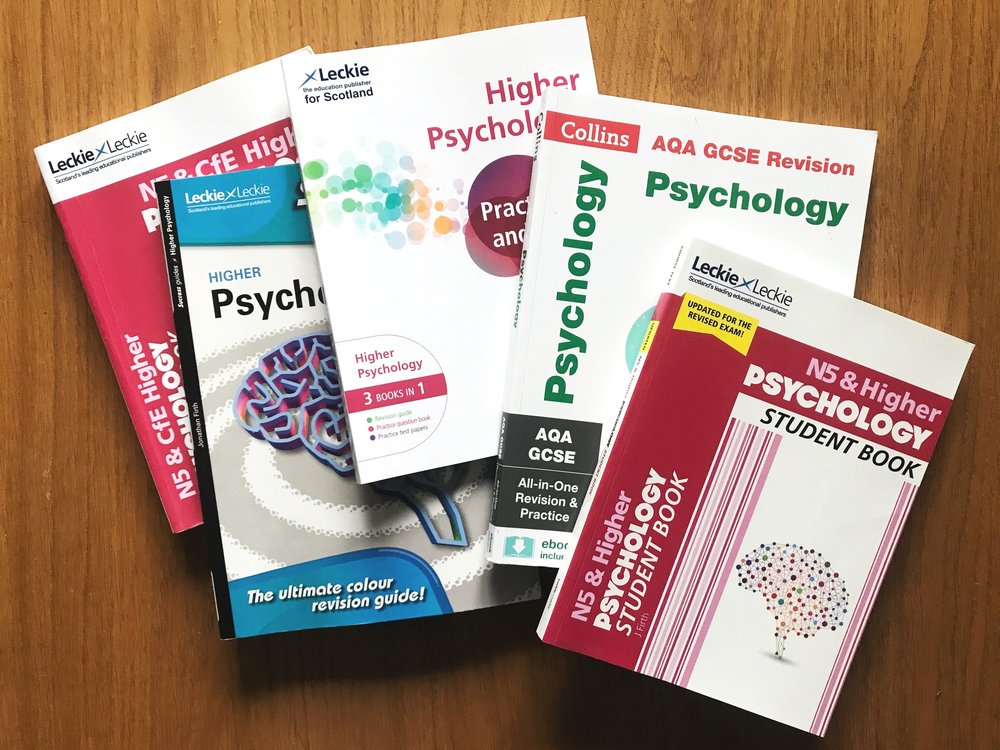

My own school psychology textbooks, including books for the Higher and GCSE courses. There are also a wide range of resources for A-Level Psychology.

I’ve been teaching Psychology at secondary school level for almost two decades. This article discusses routes into teaching the subject. It has a particular focus on the school system here in Scotland, but most of the points are relevant to other settings too.

I became interested in teaching when I was an undergraduate, through the experience of giving talks to my Honours class and leading small seminars – I found that I enjoyed explaining concepts and research to others. If you also enjoy working with others and sharing your knowledge of Psychology, perhaps you should consider a career as a school psychology teacher or college lecturer. I will try to explain in simple terms how best to follow these paths, and what might be involved.

Changing Routes into school teaching

It used to be very difficult to get into Psychology teaching at school level. To teach in Scotland, it is necessary to complete a teaching diploma and be accredited by the General Teaching Council, Scotland (GTCS), and historically, this proved to be something of a barrier for graduates with a single honours degree in Psychology. Until recently there was no professional graduate diploma in education (PGDE) in the subject in Scotland; some psychology graduates trained as a primary teachers, though they tend to stay in the primary sector once they have started out there, rather than moving to secondary where the discipline is taught as a discrete subject.

In contrast, those with a joint honours degree combining it with a traditional ‘school’ subject (e.g. biology) had the option of training in the other subject, with a view to teaching Psychology it once they were actually in a school. Indeed, it was easier (and much more common) not to have a degree in Psychology at all, but instead to add it to an existing teaching qualification in another subject as part of the professional registration process (which only requires 2 years of university study in psychology).

This situation made it harder for psychology specialists to enter the profession, and fortunately it is now changing. For the past few years there have been a small number of funded teacher training posts specifically in Psychology or Social Sciences south of the border, and since 2016, the University of Strathclyde has run Scotland’s first – and so far, only – PGDE in Secondary Psychology.

The FE sector

The college sector has a longer tradition of psychology teaching, and there is a well-established teacher education course called the TQFE (teaching qualification in further education) available. Some colleges may be willing to employ psychology graduates without this and allow them to train on the job, especially if they already have classroom experience.

It is worth noting, too, that many college lecturers in Scotland deliver Psychology in secondary schools, going out weekly to deliver the N5 and Higher to schools who do not have their own psychology departments. In some cases, it is the pupils that travel to college once or twice a week. Because of this crossover between the sectors, it would be an advantage for lecturers to be GTCS registered as described above. In fact, I know of some college staff whose entire teaching timetable consists of school visits.

Nature of the courses

If you didn’t do Psychology at school, you may wonder what exactly is taught on a school psychology course. Actually, even if you did, it is likely to have changed by now! New and much changed versions of the popular Higher, International Baccalaureate, GCSE and A-Level courses have all recently been launched.

In terms of the Higher, there is a big focus on research. 33% of the grade is awarded for an individual research project which is written up in the same format as reports at university. The exam also tests research methods, although it does so in the context of questions on topic areas, and inferential statistics are optional at this level. Mandatory topics include ‘conformity & obedience’, and ‘sleep & dreams’, and learners need to be aware of different theoretical approaches such as the biological and cognitive perspectives. Naturally, theories and research evidence are covered, though fewer than at undergraduate level, and there is more of an emphasis on classic studies than recent work. Two optional topics can be chosen; prejudice, relationships and memory are popular choices. The National 5 course follows the same structure, though the level of demand is lower and the option topics are different.

The A-Level is essentially similar, but as a 2-year course it is more demanding than the Higher. Statistical tests are integral to the A-Level, and it includes more topics and a greater emphasis on approaches (e.g. the behaviourist approach) and debates (e.g. nature vs. nurture). It also places more emphasis on the exam – the exam boards south of the border controversially dropped their project work from the syllabus a number of years ago. GCSE Psychology is less conceptual and more content-focused, with a really good range of topics (note that topics and course structure for both A-Level and GCSE vary depending on the exam board).

Most college lecturers in Scotland deliver the HNC or HND in Social Sciences (Higher National Certificate/Diploma – equivalent in level to 1st year or 2nd year of a degree respectively), including elements of Psychology but also of disciplines such as Politics and Sociology. Some have their own degree programmes, too.

As a new teacher, it can be hard to get up to speed on the various theories and research covered in school courses. A degree is an excellent foundation, but there will be content that you haven’t covered since 1st year, if at all. You may also be in the position of having to create a lot of teaching materials initially; I set up a school course from scratch and it was a tough couple of years at the start, but became much easier once things were up and running. Which brings me on to…

Life as a psychology teacher

Networking and sharing resources are always helpful in education, but are particularly important when if you are the only teacher of the subject in your school (and many schools have only one psychology teacher, or two at the most). Over the past couple of years, a group of over 200 psychology teachers and lecturers in Scotland have established an email network, asking each other questions and providing peer support. We share resources directly via email, Dropbox, and Google Drive. YouTube is great for clips of psychology experiments or relevant TED talks, and there are textbooks for all of the major courses (including my own for GCSE and Higher). The British Psychological Society is also supportive, offering free membership and other resources to school departments.

There are also regular conferences. A UK-wide organisation called the Association for the Teaching of Psychology holds a large conference every summer; it has a Scottish branch which runs its own events, and there is also a Europe-wide ‘confederation’ of psychology teacher associations from different countries with a biannual conference.

I have learned a lot from working as an exam marker, both from talking to experienced staff at marker events and from reading students’ work on the exam scripts themselves! There is always something new which can stimulate ideas for your own teaching.

Life as a school psychology teacher can become very exam-focused. With most classes sitting the exams in May or June, the year revolves around prelims, coursework and the exams themselves. However, some schools have begun to introduce the subject to younger years, which will lead to more variety for the teacher, and a better foundation for the learners. Hopefully it will eventually become the norm for Psychology to be a part of the curriculum right from S1.

Prospects for the subject

For now, Psychology remains a relatively small subject in Scotland – in the top 20 of subjects in terms of number of Higher candidates with around 4000 entries annually, and uncommon at earlier stages of school. However there is huge potential for it to expand; the A-Level is the 4th largest subject in terms of entries, with only Maths, English and Biology recording higher numbers.

The main reason for the difference north of the border is that fewer schools offer it, partly because it is newer, but again this is changing, with graduates from the Strathclyde PGDE pioneering the subject in several schools who had not offered it before. If Psychology was on offer in every school in the country, the Higher could easily be studied by over double the current number of candidates. I have seen the N5 course being newly launched in a number of schools over recently years, and proving very popular. All of this suggests that there will be many more opportunities for new teachers in years to come.

It is perhaps surprising that there isn’t an Advanced Higher qualification in psychology – available in all other subjects of comparable size – particularly as the subject tends to be (in my view, wrongly) viewed as a sixth-year subject. It would be good to see SQA introduce this in the future; I have had many students who would like to study Psychology but could not, either because they had already done the Higher in S5 and there was no course to move on to in S6, or because their university conditions required Advanced Highers only. A small number of centres offer A-Level in S6, but this comes with logistical difficulties.

If Psychology is taught to 5th and 6th year school pupils, why stop there? As noted above, some schools are now offering the subject to 3rd and 4th year pupils, and in the future I’d also like to see Psychology taught to even younger pupils too, including at primary. This could make use of a ‘psychology for children’ approach (analogous to a well-established ‘philosophy for children’ programme).

Indeed, psychology can benefit school learners at all stages. I’d love to see the subject develop and be properly recognised throughout the curriculum – and enthusiastic generation of new teachers will play a key role in that process.

An earlier version of this article appeared as a guest article in the University of St Andrews’ “Maze” magazine for students.