I’ve been thinking a lot about slowness and refusal; in technology, in practice, in life more generally.

Slowness and refusal was the focus of an Edinburgh Futures Institute Contested Computing event earlier this month on Imagining Feminist Technofutures, with Sharon Webb, Usha Raman, Mar Hicks, and Aisha Sobey. In a wide ranging discussion that questioned the dominance of techno-solutionism, the biases and inequalities that are encoded in technology, and the role of education in countering these historical structures of dominance, the panel touched on feminist refusal and the importance of “slowing down” development cycles in order to hold tech companies to account and give corrective measures and ways of refusal a chance to thrive. Slowing down can be seen as a form of progressive innovation, a way to offer resistance, and academia is a space where this can be brought to life.

(I couldn’t help thinking about my own domain of open education where there has always been a tendency to privilege techno-solutionism as the height of innovation. Going right back to the early days of learning objects, there has been a tension between those who take a programmatic, content-centric view of open education, and those who focus more on the affordances of open practice. Proselytising about the transformative potential of generative AI education is just the latest incarnation of this dichotomy.)

Recognising the value of refusal brought to mind a point Helen Beetham made in her ALT Winter Summit keynote last December, which I’m still thinking about, slowly.

Helen called for universities to share their research and experience of AI openly, rather than building their own walled gardens, as this is just another source of inequity. As educators we hold a key ethical space. We have the ingenuity to build better relationships with this new technology, to create ecosystems of agency and care, and empower and support each other as colleagues.

Helen ended by calling for spaces of principled refusal within education. In the learning of any discipline there may need to be spaces of principled refusal, this is a privilege that education institutions can offer.

During the Technofutures event, Sharon Webb asked “where is the feminist joy we can take from these things? How can we share our feminist practice and make community accessible?”

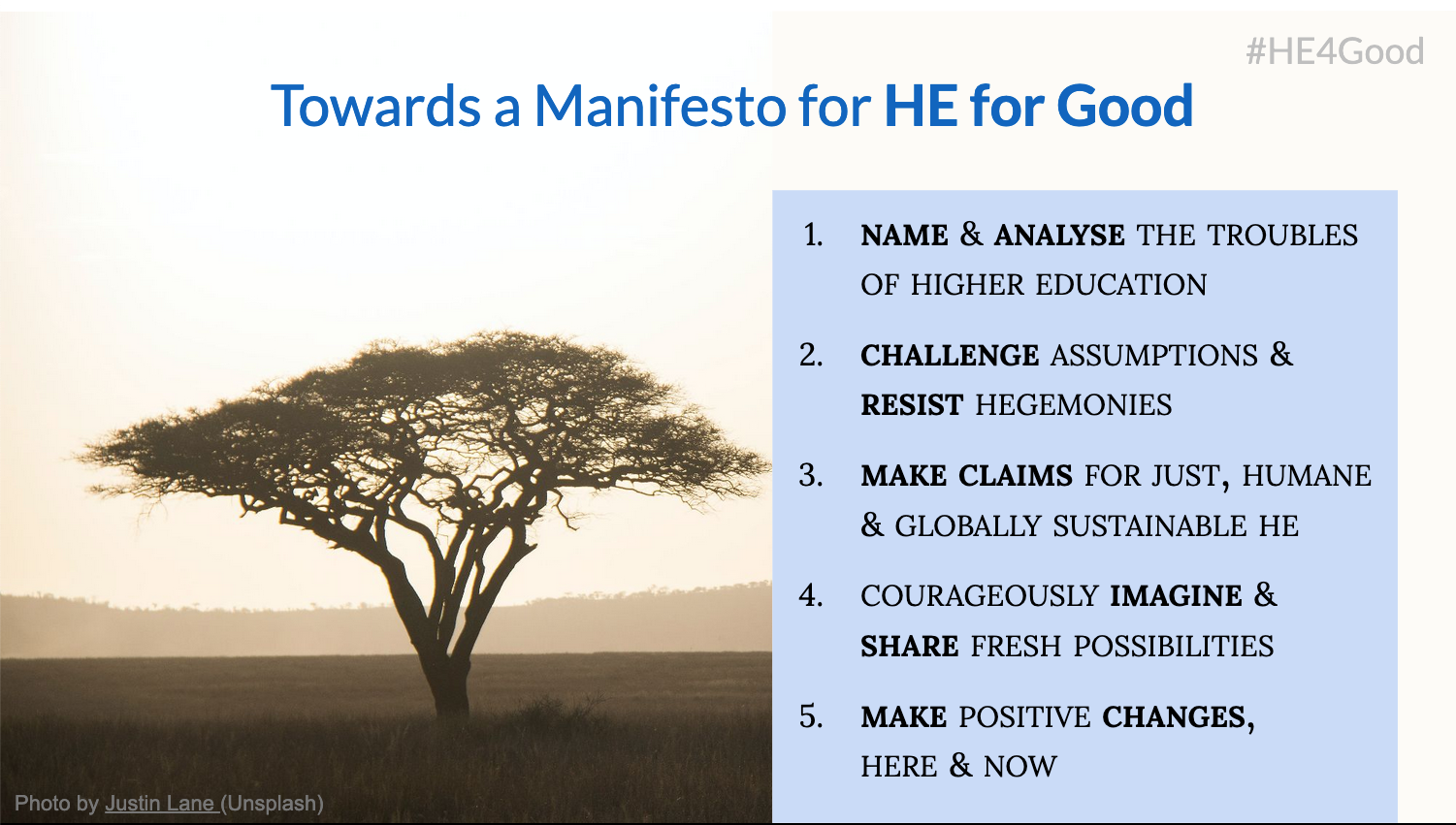

This is a question that Frances Bell, Guilia Forsythe, Lou Mycroft, Anne-Marie Scott and I tried to address in the chapter we contributed to Laura Czerniewicz and Catherine Cronin’s generative book Higher Education for Good. “HE4Good assemblages: FemEdTech Quilt of Care and Justice in Open Education” explores the creation of the FemEdTech quilt assemblage through a “slow ontology of feminist praxis”. Quilting, and other forms of communal making, have always provided a space for women to share their skill, labour and practice on their own terms outwith the strictures of capitalist society and institutions that seek to exploit and appropriate their labour. These are also a space that necessarily invite us to slow down. Contributors to the FemEdTech quilt were

“compelled by the process to decelerate, helping them to curate, to stitch, to draw, to write, and to think. We acknowledge the pressures of the time: being creative in neoliberal times is itself a form of resistance.

…

Resistance requires radical rest (rest for health, rest for hope). The slow ontology of the assemblage required waves and pauses which allowed space to think. This may be the most crucial resistance of all in an industrialised HE which fills every potential pause with compliance activity. Feminists create, feminists resist, and feminists celebrate difference.”

This is how we can share our feminist joy; by decelerating, by sharing our feminist practices and making our communities accessible, through networks like FemEdTech.

Of course it’s difficult to disentangle the process of sharing practice and building community from the technology, and particularly the social media, that mediates so much of our lives. The exodus of users from X to Bluesky at the end of the year promoted some interesting conversations on Mastodon about the role of different social media platforms. I particularly appreciated this conversation with Robin de Rosa and Kate Bowles about the ability of Mastodon to provide a space for “big thinking” and slowing down.

I’ve been forced to embrace slowness on a more personal level this year as a result of serious ongoing health issues. Its been a salutary reminder that although our practice is mediated by technology, it is still embodied and that ultimately it’s that embodiment that governs our ability to work, create, and contribute to our communities. I’m still trying to figure out what all this means on both a personal and professional level; how to make slowing down and refusal a conscious progressive act, and to find the joy in embracing radical rest for health and hope. Like the FemEdTech quilt and network, it’s a slow process of becoming.

(@Puiyin)

(@Puiyin)