Hands of Hope, Cork, CC BY, Lorna M. Campbell

Last week the OER24 Conference took place at the Munster Technological University in Cork and I was privileged to go along with our OER Service intern Mayu Ishimoto.

The themes of this year’s conference were:

- Open Education Landscape and Transformation

- Equity and Inclusion in OER

- Open Source and Scholarly Engagement

- Ethical Dimensions of Generative AI and OER Creation

- Innovative Pedagogies and Creative Education

The conference was chaired with inimitable style by MTU’s Gearóid Ó Súilleabháin and Tom Farrelly, the (in)famous Gasta Master.

The day before the conference I met up with a delegation of Dutch colleagues from a range of sectors and organisations for a round table workshop on knowledge equity and open pedagogies. In a wide ranging discussion we covered the value proposition and business case for open, the relationship between policy and practice, sustainability and open licensing, student engagement and co-creation, authentic assessment and the influence of AI. I led the knowledge equity theme and shared experiences and case studies from the University of Edinburgh. Many thanks to Leontien van Rossum from SURF for inviting me to participate.

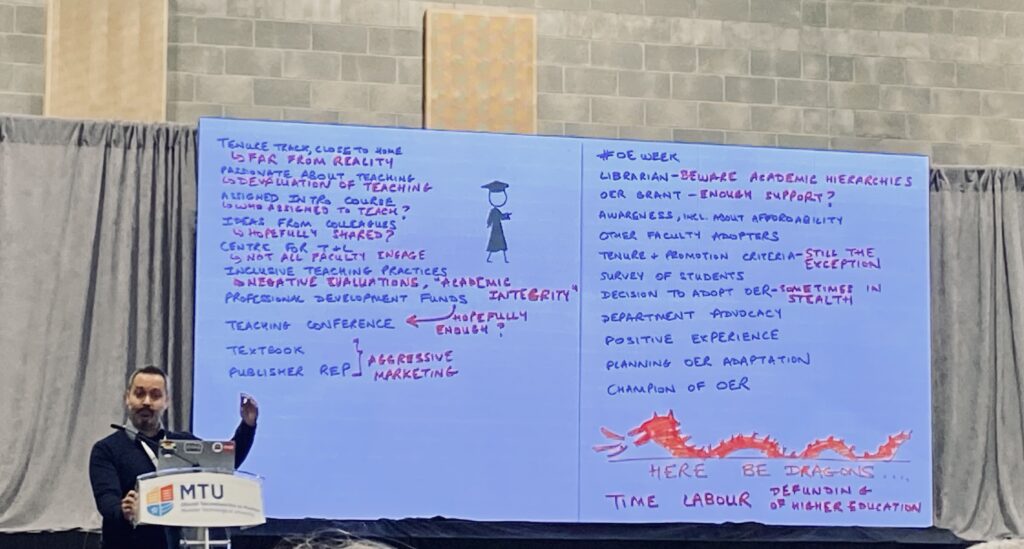

A Cautionary Fairy Tale

The conference opened the following day with Rajiv Jhangiani’s keynote, “Betwixt fairy tales & dystopian futures – Writing the next chapter in open education“, a cautionary tale of a junior faulty member learning to navigating the treacherous path between commercial textbook publishers on the one hand and open textbooks on the other. It was a familiar tale to many North American colleagues, though perhaps less relatable to those of us from UK HE where the model of textbook use is rather different, OER expertise resides with learning technologists rather than librarians, OER tends to encompass a much broader range of resources than open textbooks, and open resources are as likely to be co-created by students as authored by staff. However Rajiv did make several point that were universal in their resonance. In particular, he pointed out that it’s perverse to use the moral high ground of academic integrity to defend remote proctoring systems that invade student privacy, and tools that claim to identify student use of AI, when these companies trample all over copyright and discriminate against ESL speakers. If we create course policies that are predicated on mistrust of students we have no right to criticise them for being disengaged. Rajiv also cautioned against using OER as a band aid to cover inequity in education; it might make us feel good but it distracts us from reality. Rajiv called for ethical approaches to education technology, encouraging us not to be distracted by fairy tales, but to engage with hope and solidarity while remaining firmly grounded in reality.

Rajiv Jhangiani, OER24, CC BY Lorna M. Campbell.

Ethical Dimensions of Generative AI and OER Creation

Generative AI (GAI) loomed large at the conference this year and I caught several presentations that attempted to explore the thorny relationship between openness and GAI.

UHI have taken a considered approach by developing policy, principles and staff and student facing guidance that emphasises ethical, creative, and environmentally aware use of generative AI. They are also endorsing a small set of tools that provide a range of functionality and stand up to scrutiny in terms of data security. These include MS Copilot, Claude, OpenAI ChatGPT, Perplexity, Satlas and Semantic Scholar. Keith Smyth, Dean of Learning & Teaching at UHI, outlined some of the challenges they are facing including AI and critical literacy, tensions around convenience and creation, and the relationship between GAI and open education. How does open education practice sit alongside generative AI? There are some similarities in terms of ethos; GAI repurposes, reuses, and remixes resources, but in a really selfish way. To address these ambiguities, UHI are developing further guidance on GAI and open education practice and will try to foster a culture that values and prioritises sharing and repurposing resources as OER.

Patricia Gibson gave an interesting talk about “Defending Truth in an Age of AI Generated Misinformation: Using the Wiki as a Pedagogical Device”. GAI doesn’t know about the truth, it is designed to generate the most most accurate response from the available data, if it doesn’t have sufficient data, it simply guesses or “hallucinates”. Patricia cautioned against letting machines flood our information channels with misinformation and untruth. Misinformation creates inaccuracy and unreliability and leads us to question what is truth. However awareness of GAI is also teaching us to question images and information we see online, enabling us to develop critical digital and AI literacy skills. Patricia went on to present a case study about Business students working collaboratively to develop wiki content, which echoed many of the findings of Edinburgh’s own Wikipedia in the curriculum initiatives. This enabled the students to co-create collaborative knowledge, develop skills in sourcing information, curate fact-checked information, engage in discussion and deliberation, and counter misinformation.

Interestingly, the Open Data Institute presented at the conference for what I think may be the first time. Tom Pieroni, ODI Learning Manager, spoke about a project to develop a GAI tutor for use on an Data Ethics Essentials course: Generative AI as an Assistant Tutor: Can responsible use of GenAI improve learning experiences and outcomes?

CC BY SA, Tom Pieroni, Open Data Institute

One of the things I found fascinating about this presentation was that while there was some evaluation of the pros and cons of using the GAI tutor, there was no discussion about the ethics of GAI itself. Perhaps that is part of the course content? One of the stated aims of the Assistant AI Tutor project is to “Explore AI as a method for personalising learning.” This struck me because earlier in the conference someone, sadly I forget who, had made the sage comment that all too often technology in general and AI an particular effectively remove the person from personalised learning.

Unfortunately I missed Javiera Atenas and Leo Havemann’s session on A data ethics and data justice approach for AI-Enabled OER, but I will definitely be dipping in to the slides and resources they shared.

Student Engagement and Co-Creation

Leo Havemann, Lorna M. Campbell, Mayu Ishimoto, Cárthach Ó Nuanáin, Hazel Farrell, OER24, CC0.

I was encouraged to hear a number of talks that highlighted the importance of enabling students to co-create open knowledge as this was one of the themes of the talk that OER Service intern Mayu Ishimoto and I gave on Empowering Student Engagement with Open Education. Our presentation explored the transformative potential of engaging students with open education through salaried internships, and how these roles empower students to go on to become radical digital citizens and knowledge activists. There was a lot of interest in Information Services Group’s programme of student employment and several delegates commented that it was particularly inspiring to hear Mayu talking about her own experience of working with the OER Service.

Open Education at the Crossroads

Laura Czerniewicz and Catherine Cronin opened the second day of the conference with an inspiring, affirming and inclusive keynote The Future isn’t what it used to be: Open Education at a Crossroads OER24 keynote resources. Catherine and Laura have the unique ability to be fearless and clear sighted in facing and naming the crises and inequalities that we face, while never losing faith in humanity, community and collective good. I can’t adequately summarise the profound breadth and depth of their talk here, instead I’d recommend that you watch to their keynote and read their accompanying essay. I do want to highlight a couple of points that really stood out for me though.

Laura pointed out that we live in an age of conflict, where the entire system of human rights are under threat. The early hope of the open internet is gone, a thousand flowers have not bloomed. Instead, the state and the market control the web, Big Tech is the connective tissue of society, and the dominant business model is extractive surveillance capitalism.

AI has caused a paradigmatic shift and there is an irony around AI and open licensing; by giving permission for re-use, we are giving permission for potential harms, e.g. facial recognition software being trained on open licensed images. Copyright is in turmoil as a result of AI and we need to remember that there is a difference between what is legal and what is ethical. We need to rethink what we mean by open practice when GAI is based on free extractive labour. Having written about the contested relationship of invisible labour and open education in the past, this last point really struck me.

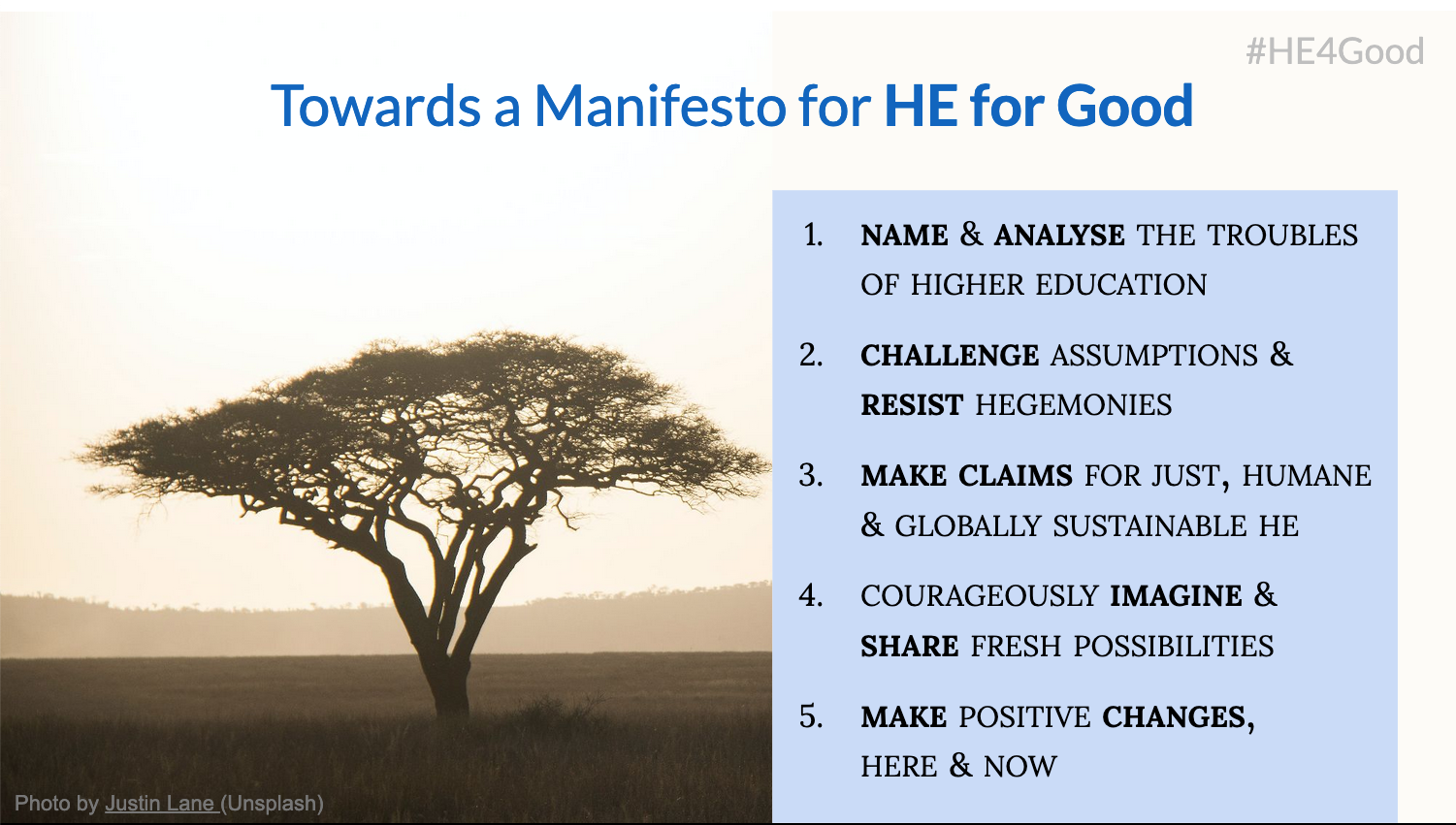

HE for Good was written as an antidote to these challenges. Catherine & Laura drew together the threads of HE for Good towards a manifesto for higher education and open education, adding:

“When we meet and share our work openly and with humility we are able to inspire each other to address our collective challenges.”

CC BY NC, Catherine Cronin & Laura Czerniewicz, OER24

Change is possible they reminded us, and now is the time. We stand at a crossroads and we need all parts of the open education movement to work together to get us there. In the words of Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and current Chair of the Elders:

“Our best future can still lie ahead of us, but it is up to everyone to get us there.”

Catherine Cronin & Laura Czerniewicz, OER24, CC BY, Lorna M. Campbell.

The Splintering of Social Media

One theme that emerged during the conference is what Catherine and Laura referred to as the “splintering of social media”, with a number of presenters exploring the impact this has had on open education community and practice. This splintering has lead people to seek new channels to share their practice with some turning to the fediverse, podcasting and internet radio. Blogging didn’t seem to feature quite as prominently as a locus for sharing practice and community, but it was good to see Martin Weller still flying the flag for open ed blogging, and I’ve been really encouraged to see how many blog posts have been published reflecting on the conference.

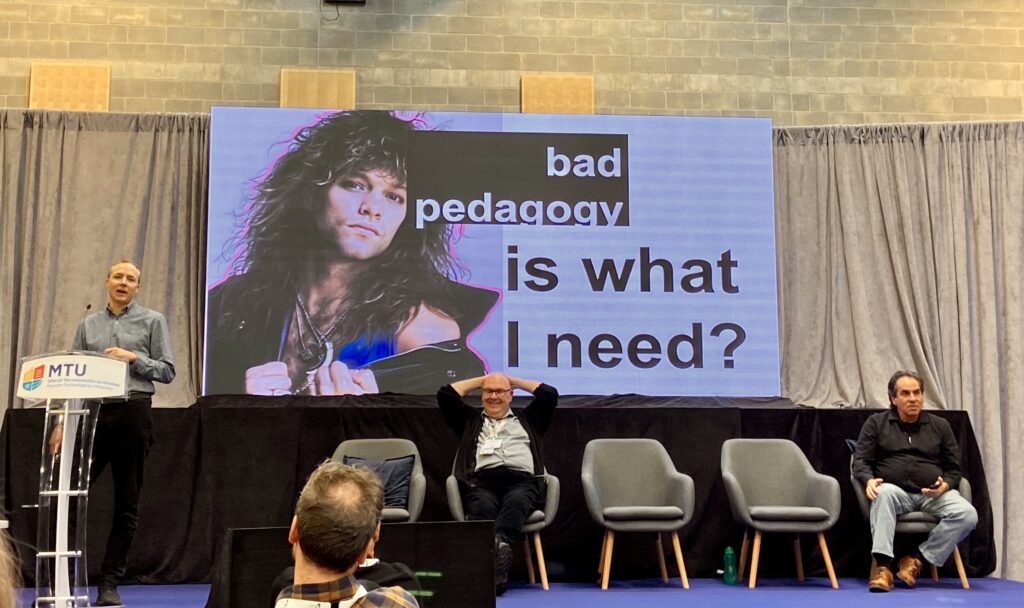

Gasta!

The Gasta sessions, overseen by Gasta Master Tom Farelly, were as raucous and entertaining as ever. Every presenter earned their applause and their Gasta! beer mat. It seems a bit mean to single any out, but I can’t finish without mentioning Nick Baker’s Everyone’s Free..to use OEP, to the tune of Baz Luhrmann “Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen)”, Alan Levine’s Federated, and Eamon Costello’s hilarious Love after the algorithm: AI and bad pedagogy police. Surely the first time an OER Conference has featured Jon Bon Jovi sharing his thoughts on the current state of the pedagogical landscape?!

Eamon Costello, Jon Bon Jovi, Tom Farrelly, Alan Levine, OER24, CC BY, Lorna M. Campbell

The closing of an OER Conference is always a bit of an emotional experience and this year more so than most. The conference ended with a heartfelt standing ovation for open education stalwart Martin Weller who is retiring and heading off for new adventures, and a fitting and very lovely impromptu verse of The Parting Glass by Tom. Tapadh leibh a h-uile duine agus chì sinn an ath-bhliadhna sibh!

Martin Weller, Tom Farrelly, Gearóid Ó Súilleabháin, CC BY, Lorna M. Campbell, OER24.

* The title of this blog post is taken from this lovely tweet by Laura Czerniewicz.